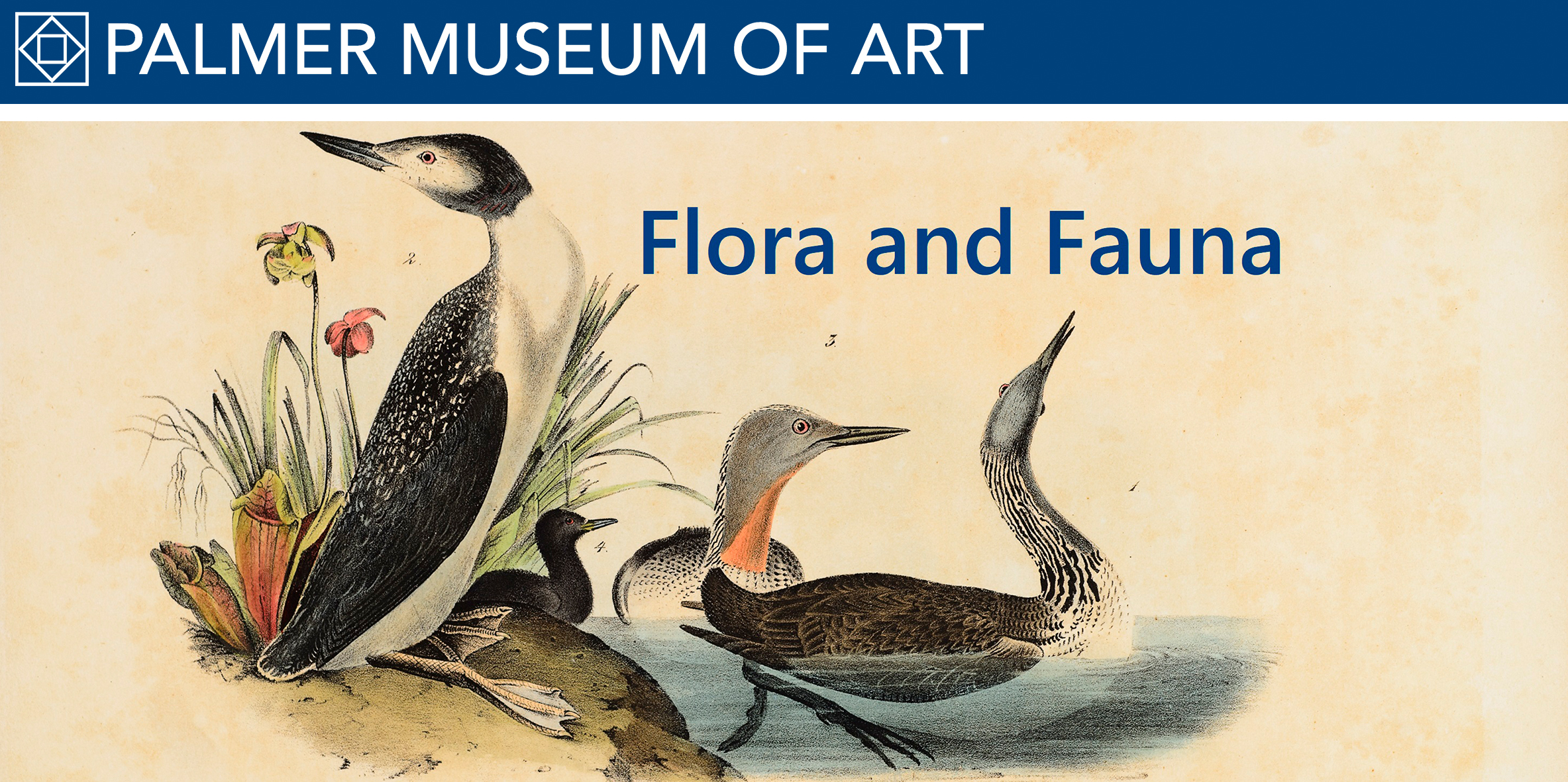

Flora and Fauna

May 19–August 16, 2015

The practice of illustrating natural history extends back several thousand years. Pliny the Elder, in his encyclopedic Naturalis Historia published in c. 79 AD, tells us that the ancient Greeks regularly decorated their treatises on medicinal botanicals with drawings of key specimens. But the precise rendition of flora and fauna dates only to the eighteenth century, when the codification of scientific methods begun in the previous century laid the foundation for increscently accurate imagery of the natural world. Indeed, the title of this exhibition is rooted in the work of one of the major scholars from this period, botanist Carl Linnaeus, whose studies of the plants and animals of his native Sweden, Flora Svecica (1745) and Fauna Svecica (1746), introduced the method of naming the genus and species of living things that is still in use today. While Linnaeus scarcely illustrated his texts—the first featured a single foldout plate; the second, just two—many of his contemporaries lavishly embellished their books with images of the subjects under study. Le Comte Buffon’s massive Histoire naturelle, générale et particulière, for example, represented here by a colored etching of the Pennsylvania Cougar (Puma concolor—the Nittany Lion is one), was adorned at its completion in 1789 with well over 2000 plates.

Perhaps the best-known illustrator of flora and fauna, certainly in the United States, was John James Audubon, whose Birds of America, published between 1827 and 1839, is considered by many to be the finest ornithological study ever completed. The exhibition features several examples from both the original double elephant edition and the later, and smaller, royal octavo version. Also on view are several sheets by Audubon’s British counterpart, John Gould, whose Birds of Europe offered a creditable response to Audubon’s Birds, as well as a single but spectacular engraving from Alexander Wilson’s American Ornithology, an important study that predated Audubon’s by several decades. Earlier examples of flora and fauna round out the exhibition, including several sheets from an early sixteenth-century Flemish Book of Hours, beautifully decorated with readily identifiable flowers, birds, and insects; illustrations of imaginary animals from a seventeenth-century book on the Americas; and a page from Jacob Meydenbach’s 1491 Hortus sanitatis, or Garden of Health, bearing woodcut vignettes of beasts and herbs that even in the fifteenth century were likely considered to be of dubious efficacy as curatives.

With the exception of the intaglio from Wilson’s American Ornithology, which is on loan from a private collection, all of the prints and drawings on view in Flora and Fauna have been selected from the Palmer Museum of Art’s permanent collection.

Organized by the Palmer Museum of Art. Curated by Patrick McGrady, Charles V. Hallman Senior Curator.