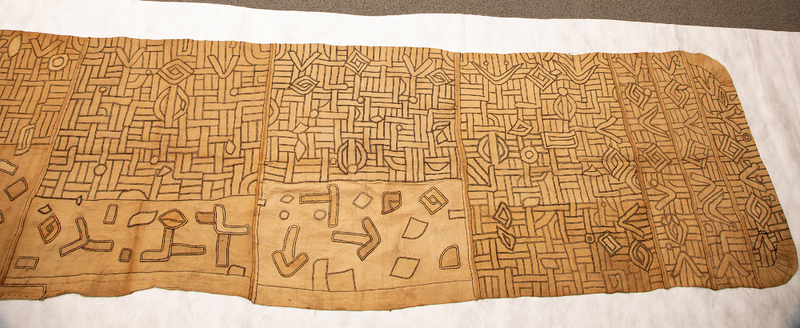

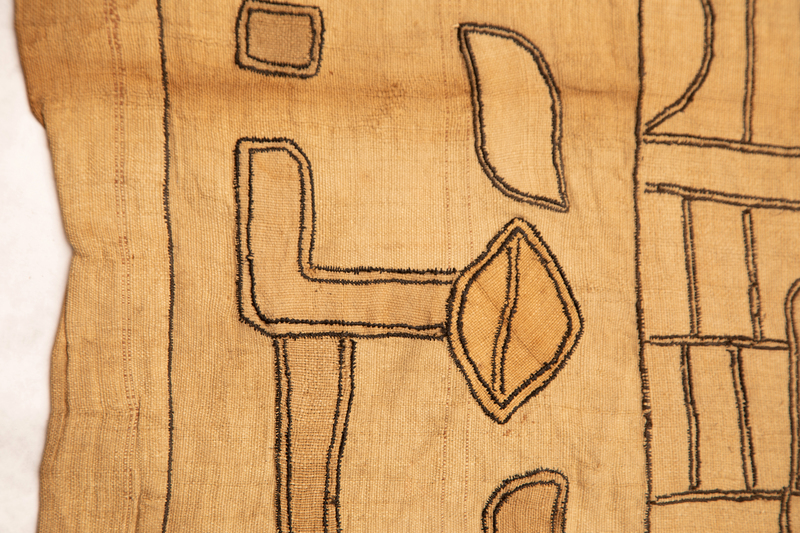

Catalogue 36

Skirt

Kuba people, Democratic Republic of the Congo

20th century

Raffia and dye; 201 x 33 inches (510.5 x 83.8 cm)

Palmer Museum of Art

Purchased from Allen and Barbara Davis

2016.88

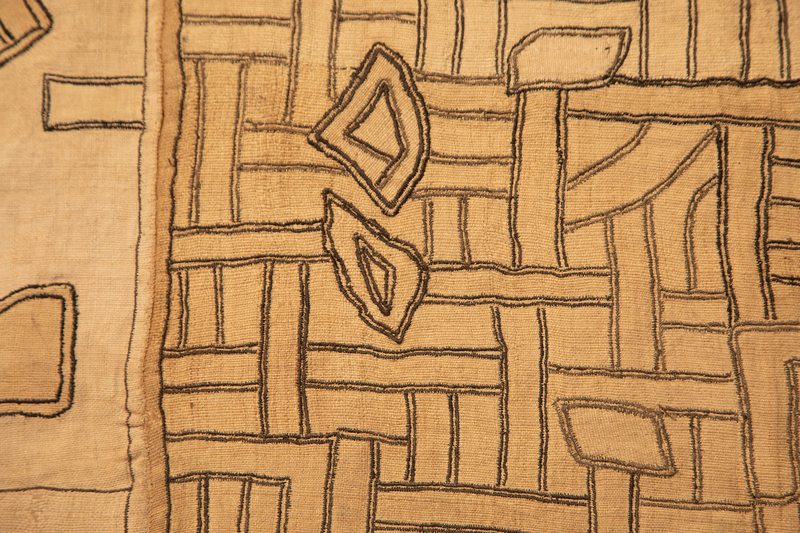

Kuba artists are renowned for inventive surface patterns, and their playfully creative applications across almost every utilitarian object, especially textiles. Elaborately decorated raffia textiles are part of the significant suite of gifts presented by family and clan members to display on the occasion of a funeral. This is one of their most common uses. The textiles, along with other costume accessories such as hats, bracelets, belts, and anklets, are exhibited when the body of a deceased person is lies in state for several days before the burial. The length, quality, and quantity of embroidery, and any associations with the individual’s specific clan or rank, are all significant. These cloths are later wrapped around or buried with the body, or sometimes saved by the family and stored for a future occasion (Darish 1989, 131–32).

For the Kuba and their trading partners, the “extraordinary amount of time expended to create beautiful objects was considered to be an intrinsic part of their value and desirability” (Binkley and Darish 2009, 123). Accordingly, a skirt usually holds more value for the number of times it may be wrapped around a body when worn as a layer in a ceremonial costume or in the funeral context. All luxury products—including this type of embroidered cloth, ceremonial textiles and clothing embellished with beads and cowrie shells, jewelry, and carved items—were considered important as trade items in the nineteenth century and earlier (Vansina 1978, 194).

In other contexts, embroidered raffia cloths were part of the annual tribute that village leaders and regional chiefs sent to the king and capital (Vansina 1978, 140); they sometimes functioned as payment in legal settlements or marriage contracts (Darish 1989, 128; Adams 1978, 30); and small squares were even traded as a form of currency.

Textile-production tasks are divided by gender, but the necessity of interdependent contributions from men and women reveals the high social and cultural value the Kuba place upon the creation of the textiles (Darish 1989, 117). Men weave raffia fiber on hand looms to form the base cloth, then both men and women knead, beat, and rub the cloth in water as a treatment for a softer and suppler material. Women are responsible for the decorative elements and designs, including embroidery and pile work with needles, appliqué, trimming, and dyes (Adams 1978, 34–36). Men and women create the designs for costumes and clothing fashioned from the embroidered and decorated textiles, primarily along gender-specific lines (Burgunder 2004, 204; Binkley and Darish 2009, 21–22; Darish 1989, 121).

As with any creative endeavor and fashion in general, styles have evolved over time, and different preferences prevail across the many different ethnic groups and regions that make up the kingdom (Adams 1978, 34; Moraga 2011, 141). However, traditional Kuba textile designs and creativity persist, because “textile production and use pattern are linked to Kuba ideas regarding social responsibility, ethnic identity, and religious belief” (Darish 1989, 118).

JMP

References

Adams, Monni. 1978. “Kuba Embroidered Cloth.” African Arts 12 (1): 24–39, 106.

Binkley, David A., and Patricia Darish. 2009. Kuba. Milan: 5 Continents Editions.

Burgunder, Lillian Maria. 2004. “This Opportunity to Dance: Kuba Textiles.” In See the Music, Hear the Dance: Rethinking African Art at the Baltimore Museum of Art, edited by Frederick John Lamp, 304. Munich: Prestel.

Darish, Patricia. 1989. “Dressing for the Next Life: Raffia Textile Production and Use among the Kuba of Zaire.” In Cloth and Human Experience, edited by Annette B. Weiner and Jane Schneider, 117–40. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Moraga, Vanessa Drake. 2011. Weaving Abstraction: Kuba Textiles and the Woven Art of Central Africa. Washington, DC: The Textile Museum.

Vansina, Jan. 1978. The Children of Woot: A History of the Kuba Peoples. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.