Catalogue 17

Crest Mask, ciwara

Bamana people, Mali

20th century

Wood; 22 7/8 x 2 1/2 x 4 inches (58.1 x 6.4 x 10.2 cm)

Collection of Allen and Barbara Davis

Ciwara (literally farming wild animal) is the mythical animal that taught the Bamana to farm. According to a well-known Bamana proverb, “Farming is the first work of humankind,” and these men’s association’s masks summarize in material form the immense importance that agriculture has played and continues to play in Bamana communities in Mali.

While the mask itself, known variously as ciwara or sogoni kun, is described as a mythical animal, its form is said to be inspired by the roan antelope (Hippotragus equinuis), with its elegant long horns. The vertical style of ciwara is generally associated with masks from the eastern Bamana regions. This more minimal pared-down male antelope form closely resembles vertical styles from Bougouni in the Segou region. When these masks are performed, they always appear in pairs of male and female, with the female carrying a small antelope, her offspring, on her back. The pair represents ideas about fertility and abundance and the belief that men and women must work together in all endeavors.

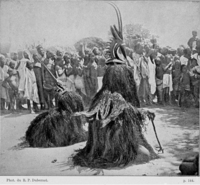

These masks were once owned and performed by the ciwara men’s association, which owned the masks, the costumes, the songs and dances, as well as ritual power objects, the boli. The masks performed in public ceremonies during the farming and harvest seasons, and there were no restrictions on who could attend the performances. Performances might take place in the fields during planting and harvest to encourage the work, or in the public square of the village to celebrate the harvest. Two young men, who were deemed champion farmers, were chosen to dance the masks, and they were accompanied by male drummers and a women’s chorus. Two young women, who were the female partners of each masker, danced behind the men and waved cloth or straw fans to diffuse the energy that was released during the most energetic portions of the dance.

The crest mask is attached to a woven raffia cap worn on the dancer’s head. He wears a fiber costume to cover his face and to partially obscure his body. He carries a long stick in each hand to mimic the front legs of the antelope, and his dance gestures often include pawing the ground as if to plant seeds. Today, in many rural communities in the Segou region, men have abandoned this men’s association, but these masks remain popular and are being incorporated into other, more secular performances. Today the image of the ciwara mask has been appropriated as a national symbol of Malian cultural identity. It appears on the currency, on commercial advertisements, as urban public monuments, and in popular paintings.

MJA

References

Arnoldi, Mary Jo. 1995. Playing with Time: Art and Performance in Central Mali. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

———. 2007. “Bamako, Mali: Monuments and Modernity in the Urban Imagination.” Africa Today 54 (2): 2–24.

Brink, James. 1981. “Antelope Headdress (Chi Wara).” In For Spirits and Kings: African Art from the Paul and Ruth Tishman Collection, edited by Susan Vogel, 24–25. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Colleyn, Jean-Paul. 2001. “The Ci-wara.” In Bamana: The Art of Existence in Mali, edited by Jean-Paul Colleyn, 201–36. New York: Museum for African Art.

Imperato, Pascal James. 1970. “The Dance of the Tyi Wara.” African Arts 4 (1): 8–13, 71–80.

———. “Sogoni Koun.” 1981. African Arts 14 (2): 38–47, 72–88.

Wooten, Stephen. 2009. The Art of Livelihood: Creating Expressive Agri-Culture in Rural Mali. Durham: Carolina Academic Press.

Zahan, Dominique. 1981. “Antelope Headdress Male (Chi Wara) and Antelope Headdress Female (Chi Wara).” In For Spirits and Kings: African Art from the Paul and Ruth Tishman Collection, edited by Susan Vogel, 22–24. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.