Catalogue 8

Helmet Mask, wan-noraogo

Mossi people, Burkina Faso

Wood and pigment; 7 1/2 x 6 5/8 x 20 7/8 inches (19 x 16.8 x 53 cm)

Smithsonian Institution, Department of Anthropology

Gift of Allen and Barbara Davis

E433672

Helmet Mask, wan-balinga

Mossi people, Burkina Faso

Wood and pigment; 6 3/4 x 6 x 1/8 x 8 x 3/8 inches (17 x 15.5 x 21.3 cm)

Smithsonian Institution, Department of Anthropology

Gift of Allen and Barbara Davis

E433667

The Mossi trace their ancestry to northern Ghana, when in the late fifteenth century horsemen from Dagomba traveled north and subjugated the indigenous farming peoples in what is now the central region of present-day Burkina Faso. They intermarried with local groups and established several states in the region, including that of Ougadougou. Today all Mossi groups speak Mooré, which was the language of the original invaders from northern Ghana.

Among the Mossi there are several mask styles. These two examples are in the Ougadougou style, which is characterized by its small, compact helmet form. This style corresponds to the area of the precolonial kingdom of the same name. In the past, museums and collectors have mistakenly attributed these masks to the Bobo, neighbors of the Mossi. These red, white, and black masks are related stylistically to groups the Mossi refer to collectively as the Gurunsi (Nuna, Lela Winama, and Kássena).

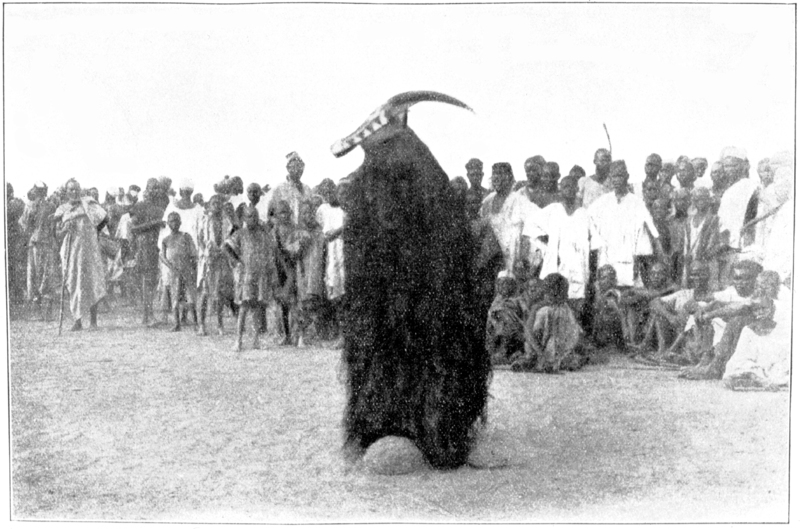

The wan-noraogo mask represents the rooster, with its characteristic carved coxcomb and pointed beak, and the wan-balinga mask, with its sagittal hairstyle, identifies this character as a woman from the neighboring Fulani herding group. These masks, however, are neither animals nor human characters, but are the clan spirits of the mask owners. In performance these masks are worn on the top of the head and do not cover the dancer’s face. A thick costume of blackened hemp fibers attached to the bottom of the mask completely hides the performer from view.

In this area, each male head of a nyonyosé lineage (those lineages who claim descent from the original farming groups) may own a clan spirit mask. Mossi masks serve as direct lines of communication between the living and the clan ancestors, and offerings are made directly to the clan mask as people seek the aid of spirits to provide many healthy children, abundant rainfall, good crops, and success in their endeavors.

Masks appear at burials of elders of the nyonyosé clans, both men and women, where they escort the corpse to the gravesite. Months later, at the funeral celebration, these masks perform for clan members and other guests to celebrate the deceased’s entry into the world of the ancestors.

MJA

References

Roy, Christopher D. 1984. “Mossi Mask Styles.” Iowa Studies in African Art 1:45–66.

———. 1985. Art and Life in Africa: Selections from the Stanley Collection. Iowa City: University of Iowa Museum of Art.

———. 1987a. Art of the Upper Volta Rivers. Meudon, France: Alain et Françoise Chaffin.

———. 1987b. “The Spread of Mask Styles in the Black Volta Basin.” African Arts 20 (4): 40–47, 89–90.

———. 2015. Mossi: Diversity in the Art of a West African People. Milan: 5 Continents Editions.

Roy, Christopher D., and Thomas G. B. Wheelock. 2007. Land of the Flying Masks: Art and Culture in Burkina Faso; The Thomas Wheelock Collection. Munich: Prestel.