Catalogue 38

Textile

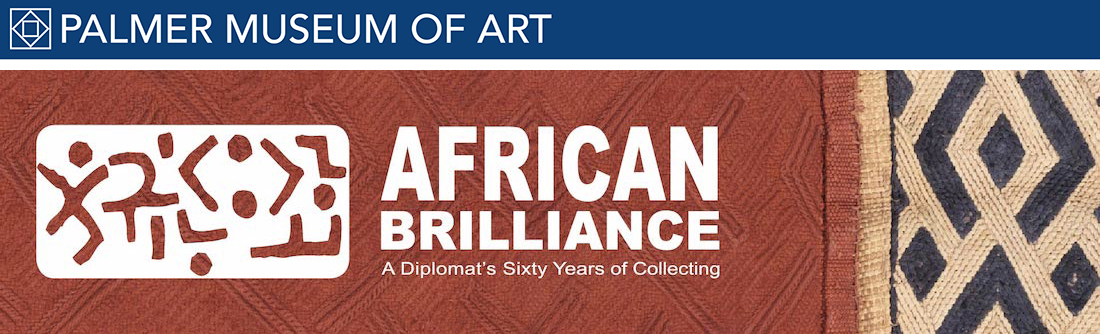

Kuba people, Democratic Republic of the Congo

20th century

Raffia and dye; 78 1/2 x 26 1/2 inches (199.4 x 67.3 cm)

Smithsonian Institution, Department of Anthropology

Gift of Allen and Barbara Davis

E434918

This imaginative variety of abstracted forms and motifs, especially appealing in their uneven and playful disbursement, is a hallmark of elaborately appliquéd raffia palm fiber Kuba textiles. This uniquely embroidered and appliquéd cloth is an example of the creativity and diverse range of surface patterns and extensive designs invented by Kuba artists to adorn textiles, buildings, woodcarvings, metalwork, and more. Their artistry is recognized as among the most prolific on the continent in embellishment and innovation. While royals and members of the nobility are the main patrons of the arts, every adult is expected to participate in the production of raffia textiles, regardless of status or location (Darish 1989, 123).

It may be noted that the common explanation for the “off-kilter placement of the floating motifs” across the expanse of cloth is indeed a “felicitous approach to dealing with the small holes and tears that resulted from pounding the raffia cloth to make it soft and supple” (Moraga 2011, 140) in many cases (Adams 1978, 30). However, the abstracted rhythm and movement resulting in the random application of the stylized forms and shapes within the broader composition also has an obvious foundation in creativity and artistic approach. As with any creative endeavor and fashion in general, styles have evolved over time, and different preferences prevail across the many different ethnic groups and regions that make up the kingdom (Adams 1978, 34; Moraga 2011, 141).

Cornet and other early sources relate that Kuba textiles “are coloured from a restricted but harmonious range, consisting of blackish-brown sepia obtained from tukula wood, yellow from another tree, and the black of charcoal” (Cornet 1971, 144–45). Adams notes, however, that colors actually appear in a much wider “range of shades: pale rose to wine red, lilac to purple, bright to dark blue, yellow to orange; depending on age and treatment, the raffia leaf varies from white to light brown” (Adams 1978, 34).

JMP

References

Adams, Monni. 1978. “Kuba Embroidered Cloth.” African Arts 12 (1): 24–39, 106.

Burgunder, Lillian Maria. 2004. “This Opportunity to Dance: Kuba Textiles.” In See the Music, Hear the Dance: Rethinking African Art at the Baltimore Museum of Art, edited by Frederick John Lamp, 304. Munich: Prestel.

Cornet, Joseph. 1971. Art of Africa: Treasures from the Congo. London: Phaidon.

Darish, Patricia. 1989. “Dressing for the Next Life: Raffia Textile Production and Use among the Kuba of Zaire.” In Cloth and Human Experience, edited by Annette B. Weiner and Jane Schneider, 117–40. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Moraga, Vanessa Drake. 2011. Weaving Abstraction: Kuba Textiles and the Woven Art of Central Africa. Washington, DC: The Textile Museum.

Tervala, Kevin, Matthew S. Polk Jr., and Amy L. Gould. 2018 "Kuba: Fabric of an Empire." Tribal Art Magazine, no. 90: 74-87.

Vansina, Jan. 1978. The Children of Woot: A History of the Kuba Peoples. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.